Post by Perfs14 on Jul 22, 2013 4:41:59 GMT

Another topical collection I really like is one that I call 'The Stamp engravers'. I really think that stamps have lost a lot at the hands of technology and false economic considerations. How much can the engraving of one issue cost when compared by the millions of units they end up printing and selling? Engraved stamps are miniature works of art, modern stamps are, by an large, just so much wallpaper IMO.

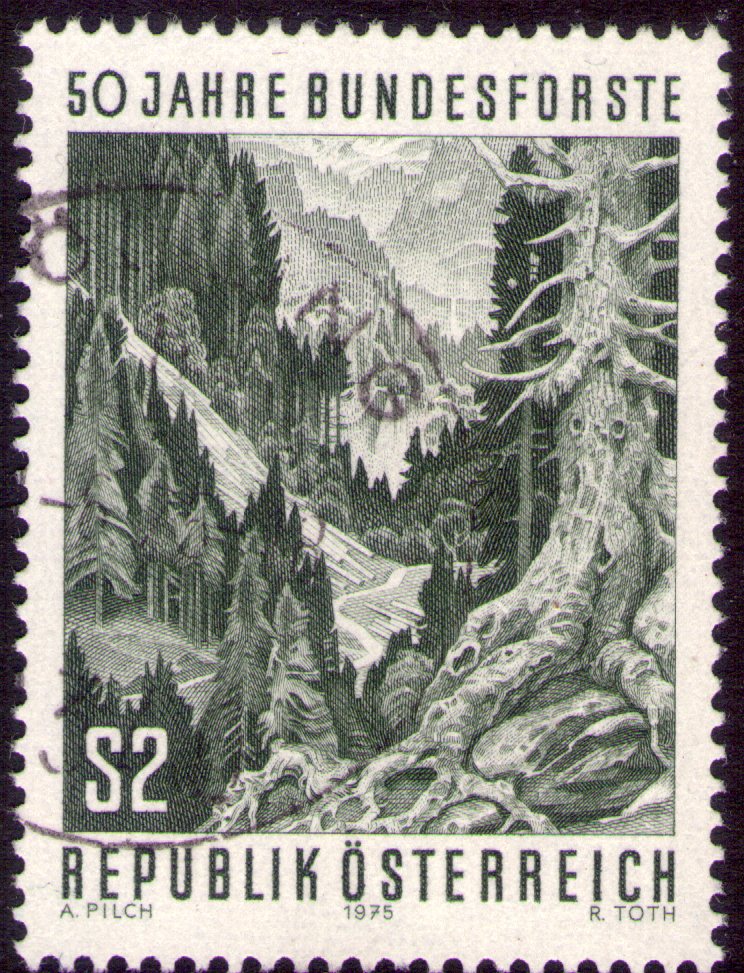

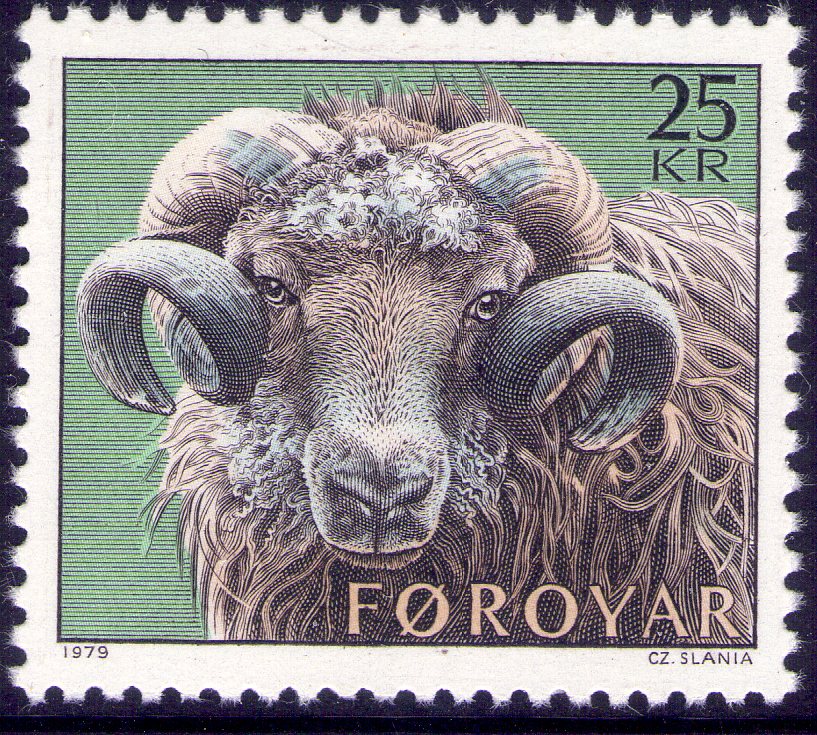

Some of my favourite engravers are: JAC Harrison; C Slania; FD Manley; Pilch and Toth; P Albuisson; and many others.

I got the following description from somewhere, but I don't remember where (old Age!)

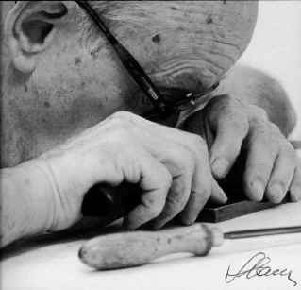

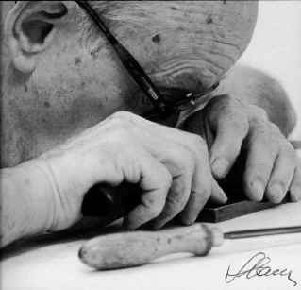

Here is Slania hard at work

Some of my favourite engravers are: JAC Harrison; C Slania; FD Manley; Pilch and Toth; P Albuisson; and many others.

I got the following description from somewhere, but I don't remember where (old Age!)

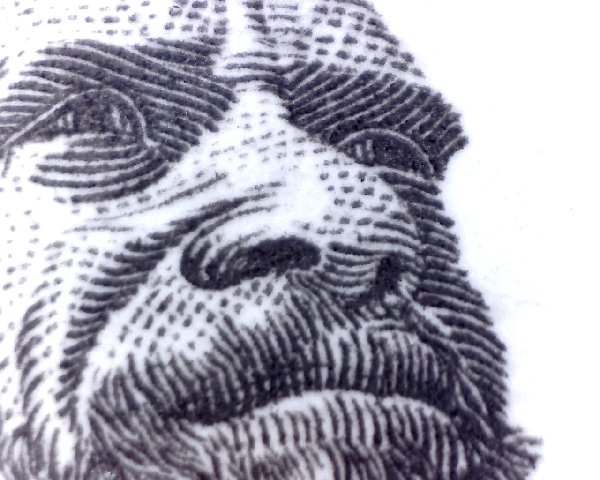

Stamp engraving is an artistic process where lines, dots and dashes are cut into a soft metal plate with a tool called a burin. The engraving is done life size and in mirror reverse. Up to 10 lines per millimetre are cut at depths varying from 0.01 to 0.08 mm to give the effects of shadows, highlights and contours. Intaglio prints, like engravings, are usually carved on metal plates with a burin, or graveur. The word “Intaglio” means “cut in.” Therefore, the black lines (e.g. the lines that show when printed) are those that are incised into the metal. One prints an Intaglio print by rolling ink into the grooves made by the burin, wiping off the excess ink, and printing the plate on damp paper. The burin is an engraving tool with a wooden handle and long metal shank with a V-shaped point.

When pushed across the metal plate, the burin creates a clean, V-shaped groove. There are many different types of burins. Some are used to make small lines, some for carving out large spaces, while others are used to make unusual shapes and lines

After the final artwork has been approved, the engraver cuts the major engraving lines as an outline into cellophane which is eight times larger than the final design size. The cut cellophane is placed over an asphalt-coated zinc plate in mirror image position. Lines are cut into the asphalt, tracing the cellophane outline, with a steel pin. The plate is placed into a nitric acid bath which etches the design into the zinc, and the asphalt is then removed. A machine called a pantograph then traces the etched outline onto a piece of soft 18.5 x 20.5 mm steel. This reduces the design by a factor of eight so that the outline is the actual size of the stamp. This crude mirror image on soft steel begins the real art of engraving.

Using a burin and magnifying glass, the engraver carves up to ten lines per millimeter into the soft steel. By carving patterns of lines, dots, and cross-hatch patterns, he forms the mirror image into the stamp-sized field of steel. Many lines, deeply carved and close together, produce heavily shaded areas on the final image. Lighter areas, such as a cheek highlight, contain relatively few shallow lines. Whatever the desired effect, the engrave must get it right the first time. There is no such thing as an eraser on a burin. This exacting process usually requires between four and six weeks per engraving. Constant proofs are pulled during this process to insure that the work is proceeding according to plan.

When pushed across the metal plate, the burin creates a clean, V-shaped groove. There are many different types of burins. Some are used to make small lines, some for carving out large spaces, while others are used to make unusual shapes and lines

After the final artwork has been approved, the engraver cuts the major engraving lines as an outline into cellophane which is eight times larger than the final design size. The cut cellophane is placed over an asphalt-coated zinc plate in mirror image position. Lines are cut into the asphalt, tracing the cellophane outline, with a steel pin. The plate is placed into a nitric acid bath which etches the design into the zinc, and the asphalt is then removed. A machine called a pantograph then traces the etched outline onto a piece of soft 18.5 x 20.5 mm steel. This reduces the design by a factor of eight so that the outline is the actual size of the stamp. This crude mirror image on soft steel begins the real art of engraving.

Using a burin and magnifying glass, the engraver carves up to ten lines per millimeter into the soft steel. By carving patterns of lines, dots, and cross-hatch patterns, he forms the mirror image into the stamp-sized field of steel. Many lines, deeply carved and close together, produce heavily shaded areas on the final image. Lighter areas, such as a cheek highlight, contain relatively few shallow lines. Whatever the desired effect, the engrave must get it right the first time. There is no such thing as an eraser on a burin. This exacting process usually requires between four and six weeks per engraving. Constant proofs are pulled during this process to insure that the work is proceeding according to plan.

Here is Slania hard at work